I still remember my first shower. It was a horrible experience. I was eight years old and all I had ever known was baths. Baths were neat and tidy ordeals where the water flowed in from below my head and—provided I didn’t splash too much—stayed below my head.

I found showers to be an entirely different beast. The water, rather than flowing as a solid stream that was easily visible and avoidable, sprayed out as nearly invisible and unavoidable droplets that seemed to have a magnetic attraction to my eyes.

I did not ask to be promoted from Junior Bath Taker to Junior Shower Taker, but my parents had set the date for my graduation and protesting made little difference. It didn’t help that my twin brother Alex loved showers and had taken one earlier that week.

Before I could draft my formal petition, let alone get anyone to sign it, I found myself staring up at the dreadful shower head just as a brave soul stares down the barrel of his executioner’s gun.

However, once the trigger was pulled and the shower head began rumbling and hissing, my courage melted away, and I was screaming before the first drop hit me.

The funny thing is that this morning, nearly ten years later, I took a shower and didn’t think twice about it. I even purposefully let the water spray on my face! It is incredible that what then seemed to be an impossible hurdle is now part of my everyday routine.

We’ve All Had “First Shower” Experiences

You probably can remember something in your own life that at the time seemed entirely beyond you. Maybe it was something as simple as tying your shoes or riding a bike without trainings wheels. Maybe it was learning to read or solving basic math problems in 2nd grade. These are things that are easy for you now, but were enormous challenges at the time.

My question for you is: What has changed? What is the difference between the enormous challenges of a child and the enormous challenges of a young adult?

What’s the difference between a difficult 2nd grade math problem for a seven-year-old and a difficult Algebra problem for a 15-year-old? Though an algebraic equation operates on a higher plateau than a double-digit multiplication problem, that is compensated for by the fact that a teenager operates on a higher plateau than a child.

Compare learning to dance with learning to walk. When you contrast the motor skills of a baby with those of a young child, you should conclude that, though dancing is more complex, it is not necessarily more difficult.

As a musician I can attest to the fact that my difficult piano pieces in Level 9 were no more arduous than my difficult pieces in Level 3. The only variance was my level of skill and tolerance for practice. It is just as difficult for a seven-year-old beginner to practice “Chopsticks” for 30-minutes as it is for a music major in college to practice Lizst’s “Hungarian Rhapsody” for three hours.

If a Baby Can Do It, Why Can’t We?

With those examples in mind, I return to my question: What has changed? What is the difference between the enormous challenges of your childhood and the enormous challenges of your young adulthood?

And perhaps a more important question: What is the difference between the way you responded to those challenges as a child and how you respond to them now?

I constantly hear fellow young adults say things like, “You know, I did Algebra 1/2, but I’m just not a math person,” or “I’m a terrible speller, my brain just doesn’t work that way.” I’ve had other teens tell me, “I’m just a quiet person. I don’t like communicating much,” and “I’m such a compulsive shopper. If I see something I like I can’t help but buy it.” Or what about, “I’m just such a blonde!”

While I don’t doubt that many teens find math, spelling, communication, self-control and intelligence incredibly difficult, I find it very hard to accept that these difficulties should begin to define their personhood.

We would think it was crazy if a toddler said, “You know, I tried to get potty-trained, but I’m just not a toilet person.” But we sympathize with a fellow teenager who says that he’s “just not a people person.”

Low Expectations Strike Again

The fact is that as we get older we begin defining our limitations as what comes easily to us—and our rate of growth in competence and character slows and falters.

When we were children our limitations were not defined by difficulty. Our limitations were not defined by failure—even repeated failure. So what has changed? Why do babies, with inferior motor skills, reasoning ability, and general physical and mental strength, have a nearly 100% success rate in overcoming their big challenges, while teenagers often falter and fail before theirs?

We Expect More of Babies Than We Do of Teens

The truth is that we are incredibly susceptible to cultural expectations and once we have satisfied our culture’s meager requirements we stop pushing ourselves.

Why does every healthy baby learn to walk while very few teenagers are sophisticated enough to have mastered the waltz? One is expected, the other is not.

Why does every normal baby overcome communication barriers by learning to talk while very few teenagers overcome barriers between themselves and their parents by learning to communicate? One is expected, the other is not.

We live in a culture that expects the basics, but nothing more. We live in a culture that expects for you to get by (i.e. be potty-trained), but not to thrive.

The challenge to you is this: Have you really found your limits or have you merely reached a point where our culture’s expectations no longer demand that you succeed?

We Are Capable of Much More Than Is Expected

If you were abandoned in a foreign country with citizens who spoke no English, you would pick up the native dialect. And if your high school required everyone to complete Advanced Calculus in order to graduate, you would find a way to do it.

Both necessity and expectations have incredible power to require much of us and make us strong, or to require little of us and make us weak. We live in a culture where few people do more than is required, yet that is the secret of effectiveness in the Lord’s service.

The application goes far beyond math and language, dancing and speaking; those are simply a few helpful examples. The important question we must ask ourselves is: “Am I unable to do certain things, or am I simply unwilling to invest the time and effort necessary to succeed?”

This Is a Serious Issue

Classifying yourself as “this-kind-of-person” or “that-kind-of-person” is one of the quickest ways to greatly increase or majorly hamper your potential. Adults who at one time decided they “just weren’t computer people” are missing out on all the convenience and power of technology.

A person who decides early in life that he is “just not a public speaker,” and then stops striving for excellence in the area of public communication, has no doubt lost dozens of opportunities to impact the lives of hundreds, if not thousands of people.

History is jammed full of examples of “extremely shy people” who not only overcame their fear of people, but also became famous leaders and communicators. Calvin Coolidge, the United States’ 30th President, is just one such example.

One of the most devastating classifications that can be made is when a person classifies themselves spiritually as “not really one of those extreme Christians.”

Millions of young people, even Christian young people, live through years of spiritual weakness and build up loads of regret simply because they found their identity in being a rebel.

Closing Thoughts

I wasn’t a “shower person” when I was eight, and I’m not sure if I’m a “campaign person” at 17, but by God’s grace and through His strength I can do anything. And so can you.

Nearly a decade after my first shower, one of the great challenges of my childhood, I find myself working long hours on four statewide races for the Alabama Supreme Court. When I find myself thinking that this current challenge is going to kill me, I just remember that I thought the same thing about my first shower. Then I smile, and keep on pushing.

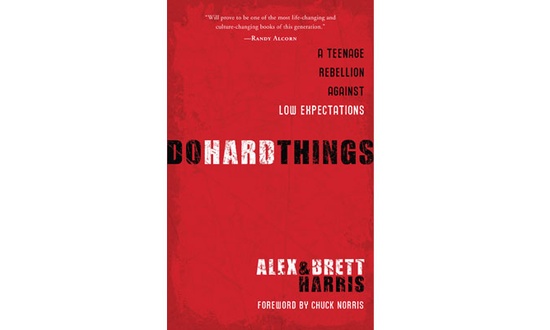

Condensed excerpt. Original article posted May 2, 2006 on The Rebelution website. Alex and Brett Harris are authors of the book Do Hard Things: A Teenage Rebellion Against Low Expectations. Used with permission.

Photo by Patrick Hendry on Unsplash