If you didn’t read Wednesday’s blog about Olympian Eric Liddell, I encourage you to go back and read that one first. The following story was first told in my book The Grace and Truth Paradox, and touches on Eric Liddell’s life after he won Olympic gold. I asked Stephanie Anderson, who works on EPM’s staff and helps with my blogs, to do some research and fill in the blanks to share more of what life was like for the children in the prison camp. She did a terrific job, and much of what she added was new to me and greatly improved this blog. Thank you, Stephanie!

Nanci and I spent an unforgettable day in England with Phil and Margaret Holder. Margaret was born in China to missionary parents with China Inland Mission. In 1939, when Japan took control of eastern China, thirteen-year-old Margaret was imprisoned in a Japanese internment camp, with no sanitation or running water, and limited food. There she remained, without her family, for six years.

“Separated from our parents, we found ourselves crammed into a world of gut-wrenching hunger, guard dogs, bayonet drills, prisoner numbers and badges, daily roll calls, bed bugs, flies, and unspeakable sanitation,” fellow prisoner Mary Taylor Previte said in a 2005 speech.

China Daily explains,

Fearing the internees could make contact with the outside world or even escape, the Japanese covered the walls with electrified wires and set up searchlights and machine guns in the guard towers. The camp was under military management and the internees were forced to wear armbands displaying a large black letter to indicate their nationalities - "B" for British, "A" for American, and so on.

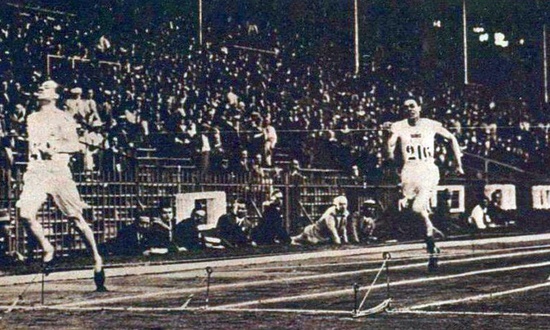

Despite the difficulties, there were glimmers of hope and joy. Margaret told us stories about a godly man called “Uncle Eric.” He tutored her and was deeply loved by all the children in the camp. We were amazed to discover that “Uncle Eric” was Eric Liddell, “The Flying Scot,” hero of the movie Chariots of Fire. Liddell shocked the world by refusing to run the one hundred meters in the 1924 Paris Olympics, a race he was favored to win. He withdrew because the qualifying heat was on a Sunday.

Liddell won a gold medal—and broke a world record—in the four hundred meters, not his strongest event. (That was the 100 meters, which Harold Abrahams won when Eric withdrew to avoid running on a Sunday.) Later Eric went as a missionary to China. When war broke out, he sent his pregnant wife and his daughters to safety. Imprisoned by the Japanese, he never saw his family in this world again. Suffering with a brain tumor, and physically wasting away, Eric Liddell died in 1945, shortly after his forty-third birthday, and less than 200 days before the camp was liberated. (This statue of Eric is in front of Weihsien Concentration Camp, which is now a museum.)

Liddell won a gold medal—and broke a world record—in the four hundred meters, not his strongest event. (That was the 100 meters, which Harold Abrahams won when Eric withdrew to avoid running on a Sunday.) Later Eric went as a missionary to China. When war broke out, he sent his pregnant wife and his daughters to safety. Imprisoned by the Japanese, he never saw his family in this world again. Suffering with a brain tumor, and physically wasting away, Eric Liddell died in 1945, shortly after his forty-third birthday, and less than 200 days before the camp was liberated. (This statue of Eric is in front of Weihsien Concentration Camp, which is now a museum.)

Through fresh tears, Margaret told us, “It was a cold February day when Uncle Eric died.”

At times it seemed unbearable to be cut off from their homes and families. But Margaret spoke with delight of “care packages falling from the sky”—barrels of food and supplies dropped from American planes.

Still, the adults of the camp knew their situation was grave as 1945 continued on. Janie Hampton writes, “The rumours of imminent peace meant even greater danger: without Japanese guards, the starving Chinese surrounding the camp would steal what little food they still had, or Communist guerrillas might kidnap the children as hostages. If defeated, the guards had been ordered to kill all prisoners, regardless of age.”

On August 17, 1945, Margaret and the other children were lined up as usual to count off for roll call. Suddenly an American airplane flew low. They watched it circle and drop more of those wonderful food barrels. But as the barrels came near the ground, the captives realized something was different. Her eyes bright, Margaret told us, “This time the barrels had legs!” The sky was full of American soldiers, parachuting down to rescue the 1,500 or so prisoners!

Mary Taylor described the scene: “Grown men ripped off their shirts and waved them at the sky. Prisoners ran in circles, wept, cursed, hugged and danced as the plane circled back. The Americans had come!”

Margaret and several hundred children rushed out of the camp, past Japanese guards who offered no resistance. Free for the first time in six years, they ran to the six soldiers and one translator, and threw themselves on their rescuers, hugging and kissing them.

Mary wrote, “We trailed our angels everywhere. My heart flipped somersaults over every one of them. We children wanted their insignias. We wanted their signatures. We wanted their buttons. We wanted souvenir pieces of parachutes. …They gave us our first taste of Juicy Fruit gum. We children chewed it and passed the sticky wads from mouth to mouth. We made them sing to us the songs of America. They taught us ‘You Are My Sunshine, My Only Sunshine.’ Fifty-nine years later, I can sing it still.” Imagine the children’s joy. Imagine the soldiers’ joy!

Janie Hampton explains:

The seven US paratroopers had been warned they were unlikely to return alive from ‘The Flying Angel’. Instead, they were hoisted onto shoulders and carried back to the camp in triumph, where they were greeted by the Salvation Army brass band playing a victory medley of national anthems which they had been practising in secret for four years.

…It took several weeks to evacuate all the internees by train and plane. The children then faced the task of tracking down their parents.

(Janie’s full article, about liberation from the camp, is well worth reading. Also, Mary Taylor Previte, great granddaughter of Hudson Taylor, wrote a touching piece about years later tracking down the paratroopers who liberated the camp.)

Now 36 years after that day we spent with the Holders, I can still vividly see Margaret’s face, full of wonder and tears of joy as she told us that story. Nanci and I were weeping along with her. Imagine the soon-to-come reunion with 19-year-old Margaret and her missionary parents, who hadn’t seen their daughter since she was 13!

God rejoices in the grace He offers us as much as we rejoice in receiving it. Whether it’s Him returning from the sky to liberate us, or drawing us to Himself through our deaths, we will be rescued and at last reunited with loved ones who’ve gone before us. We too will be taken home.

Camp photo: Wikimedia Commons | Statue photo: Wikimedia Commons